Myth #1: Quants, sophisticated algorithms, and the brightest minds in the world struggle to beat the market, and most do not. The odds are that Sam from Nebraska will not outperform the market and is better off not playing around with individual stocks. Just invest in index funds.

The problem you have, and will continue to see, is the word “invest” being interchangeably used with trading, gambling, speculating, etc…

Not everyone buying stocks is investing, certainly not long-term investing.

Many fund managers or professionals you read about do not even invest in their own fund.

Why would you invest in a fund if the fund manager isn’t doing the same?

Wall Street’s strategies differ from what you should mimic.

Investors need to understand the fundamental difference between generating income and building wealth. Typically, stocks are a wealth-building tool. Generating income from stocks requires more short-term thinking and trading strategies.

The more I see investors tinker with their portfolios or trade in and out of positions, the more confused I become. Price movement in the short term is often volatile and unpredictable. It also can be stressful and gut-wrenching. Emulating Jesse Livermore or Steve Cohen is more challenging than being the next Ronald Read or Geoffrey Holt.

As for index funds, the fundamental problem with this instrument is that it is a self-defeating investing practice. You have chosen to match the market rather than outperform it. The technical framework of most index funds is capping your gains by taking on less risk. This investment vehicle may suit some people, but I find it unacceptable.

Investing in index funds that follow a benchmark may be suitable for those who can generate a lot of income or have multiple income streams. It also may work if your portfolio is already large enough to live off without supplemental income.

You get what you deserve: The equity investor is entitled to a bigger reward because they took on more risk. Investing primarily in an index also does not change behavior or protect investors from the psychology of investing. Remember, future returns are not guaranteed. Index investing is popular because it has done well historically. Once again, a 10-15% average annual return is not guaranteed, and there is no way to assess the probability of future annual returns with pinpoint accuracy.

“A really wonderful business is very well protected against the vicissitudes of the economy over time and competition. I mean, we’re talking about businesses that are resistant to effective competition…”

“There is less risk in owning three easy-to-identify wonderful businesses than there is in owning 50 well-known, big businesses.”

– Warren Buffett

I never understood the attraction to wanting to own the entire market. It insulates yourself against a particular risk, but this diversification is unnecessary and can show a lack of focus and conviction.

Owning ten or more index funds or ETFs in your portfolios is “analysis paralysis” on steroids. There likely is a lot of overlap and bloat.

An investor must ask themselves, “What is the bigger picture?”

Diversification could help against risk, but over-diversification will likely hurt performance.

- Diluted returns: Being right on a particular holding in a fund or index won’t make a material difference. The percentage of your portfolio is too insignificant to make a meaningful move.

- Unnecessary risk protection: Some companies have a market cap equal to greater than the GDP of a small country. Not wanting to own these companies individually due to their potential to go to zero is not the best way to assess probability and risk.

- The Brock Purdy/Tom Brady effect: The 49ers got lucky when they drafted Brock Purdy in round 7, pick #262. The Patriots got lucky when they drafted Tom Brady in round 6, pick #199. If these teams were confident that these quarterbacks would turn out the way they did, they would have drafted them in much earlier rounds. These teams took a small risk that paid off handsomely. Investing has similar scenarios. Investing $5,000 isn’t a lot of skin-in-game or conviction. A $5,000 investment in Microsoft in the 90s would be well over one million dollars today – and guess what? Microsoft is, by many analysts, rated a must-own stock today! These types of gains you will never see solely investing in an index.

Myth #2: I would have to spend countless hours researching individual companies and monitoring the market daily. Why invest in stocks with the odds out of favor in beating the S&P and its proven returns?

As I explained earlier, investors who primarily invest in an index are entitled to a lower return than a direct equity shareholder in companies who take on more risk.

The research barrier people make not to invest has always perplexed me. Looking at a company’s balance sheet is a relatively simple exercise. Earning reports are quarterly events and typically get recapped in a 1-page article.

Should an investor pay attention to current events and occasionally read business news? Everyone should be doing this, but is it necessary to spend several hours a day of research to be a successful investor?

Monitoring the market is a behavioral choice, not a requirement of being an investor. If you are a long-term investor and have already committed to holding a stock for an extended period, watching the price movement of a ticker symbol every day or every hour is an addictive habit that doesn’t help advance your investing skills. A company’s fundamentals do not change daily, even monthly, so worrying about daily price fluctuation is an unnecessary risk of losing your sanity.

No one can accurately predict the future. Every investment is a bet. You will likely succeed if you have a consistent framework for investment decisions and can understand the basic plumbing of how a company makes a profit. In most cases, the research advantage is not a true advantage. There is no significant correlation between time spent researching investments and investor performance.

Investor A: Invested $100,000 in Apple Stock in 2007 due to how innovative the iPhone looked during its launch.

Investor B: Invested $100,000 in Apple Stock in 2007 after doing hours and months of research in the company, reading balance sheets, plugging numbers through several financial modeling tools, reading articles, etc.

Investor B has more formal education than Investor A. Most people would consider Investor B “smarter” than Investor A. Investor B is an extremely hard worker, shrewd at business, and knowledgeable about the stock market.

The result is the same if both investors sell at the same time. Investor B may have been likelier to sell the stock, trying to time the market by mistaking research for market noise. For a long-term investor, selling Apple stock in the past 15 years would have been a mistake, even if the reason was valid.

Putting hours of research into investments doesn’t give you a guaranteed edge in investing. Having high cognitive intelligence doesn’t correlate to investing performance.

Investing does not require you to write a 200-page dissertation to be successful. “Time in the market” refers to the holding period, not time spent researching.

Being a highly-rated brain surgeon requires years of studying and training. The same goes for being a world-class athlete or chef.

Investing is a rare activity where sitting on your ass and doing nothing pays off more than trading in-and-out of stocks. The investor’s hidden superpower comes from having discipline, patience, and emotional intelligence. The stock market is auction-driven, where you cannot drive the outcome of the results outside of buying, holding, or selling a stock.

The skillset required is a behavioral one. That is the secret weapon needed to beat the market. In all likelihood, investors A and B have already sold their positions in Apple stock for various reasons.

“On the other hand, although I have a regular work schedule, I take time to go for long walks on the beach so that I can listen to what is going on inside my head. If my work isn’t going well, I lie down in the middle of a workday and gaze at the ceiling while I listen and visualize what goes on in my imagination.”

-Albert Einstein

The problem with the research argument:

- Investors must understand that this game of critical thinking. Being an investor is a thought-job. Success comes from curiosity and continuous thought work.

- Research/Investing is subjective. One person can determine Bitcoin as ‘rat poison,’ and another person can evaluate it as the future of money.

- Investment returns directly correlate with how much risk you are willing to take, not how many hours of research you have done. No matter how much research an investor does, it cannot accurately predict future prices or events.

Myth #3: Pick the right company takes a lot of work. It is simply too risky, and the odds are not in your favor.

It is an easily debunked myth because the proof is an investor’s brokerage statement. Many professional and retail investors correctly invested early in companies like Nvidia, Apple, Amazon, and Tesla. These investors correctly picked the right company that generates life-changing results. These companies are well-known and have recognizable brands.

The problem is that most of these investors sold out too soon, indicating poor investment behavior. Investors frequently let fear and other emotions guide their strategic investment process.

Many investors also incorporate too much of a “market timing” tactical approach in their investment strategy, leading to how powerful psychological forces play into investing decisions. If the secret to wealth building is to buy and hold companies like Apple and Nvidia for a long time, why do so many people refuse to do so?

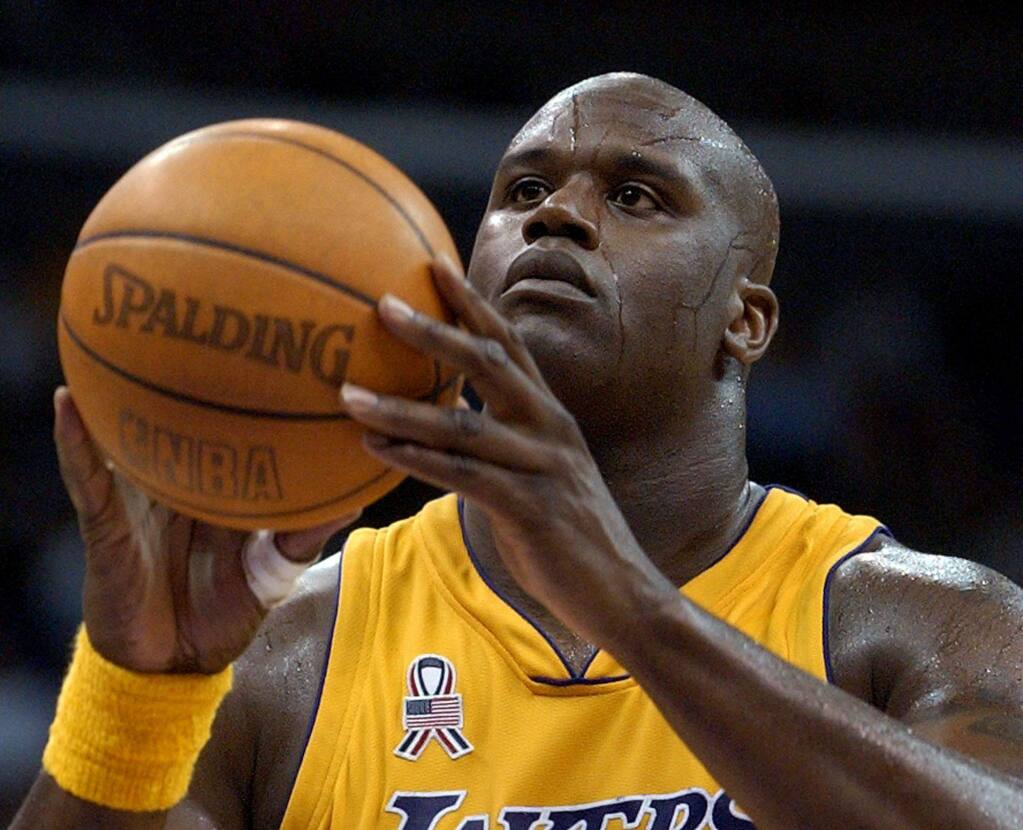

The answer is complex and simple at the same time. It would be like asking why don’t all poor free throw shooters in the NBA use the ‘Granny Shot’ free throw motion, where the player holds the ball at his waist with both hands and hoists the ball at the hoop in an underhand motion, with arms spread apart.

There is actual evidence that the Granny-style form works:

One argument in favour of shooting underhand, compared with traditional overhand, is that it requires less movement and is therefore easier to repeat. There are physics behind the form as well. Shooting underhand creates a slower, softer shot, because a two-hand shot, gripped from the sides of the ball, allows a player to impart more spin than a shooter launching the ball forward with one hand.

John Fontanella, a professor at the Naval Academy who wrote “The Physics of Basketball,” said most shots spin at two revolutions per second, but an underhand free throw will rotate three or four times per second. The additional backspin means more shots that bounce on the rim fall through.

NBA rookie brings back ‘Granny-style’ free throw

Shaq attempted 13,569 free throws in the regular season and playoffs for his career. He made 7,103, just 52.3%, which is pathetic.

If Shaq worked on and adopted the granny shot the day he started the NBA, say, his career free throw percentage would improve to 70%. That’s 2,395 more points. How many more games and championships does Shaq win by doing this?

Despite the empirical and analytical evidence, no NBA star has adopted this shooting style since 1980.

Why? The answers players give are silly:

Shaq: “I’d shoot zero percent before I’d shoot underhanded.”

“They’re gonna make fun of me.”

“That’s a shot for sissies.”

The reasons why most poor free throw shooters don’t adopt a technique that is proven to work are similar to the same reasons why most investors can’t buy and hold stocks for a long time:

Fear of standing out

Outside of your comfort zone

Pride and ego

Herd mentality

Many investors invest like Shaq shoots free throws.

Shaq didn’t want to shoot underhanded because it wasn’t for him, even though it would have dramatically helped his free throw percentage.

People want to invest successfully, but they want to do it on their own terms. The rewards are life-changing, but it requires you to embrace chaos and uncertainty. Outside of your emotions, an investor has no control over the economy or geopolitics. For many investors, long-term investing means: “If I make money, I’ll stick with it, and if I don’t, I’ll sell and do something else.”

The most significant risk factor for investors is themselves.

It is not the economy, interest rates, or the threat of war. The biggest threat to your portfolio is your behavior.

My advice:

- Do not get too cute with your overall portfolio strategy.

- Stay focused and adopt long-termism.

- If you have the discipline, adopt something similar to the coffee can strategy, an investing strategy where you mostly stay still during market volatility and sell recommendations.

Do not sell winners like Nvidia or Apple simply because someone says it is time to sell. These are companies you buy and hold, not trade. Selling a stock because someone said it’s wise to trim your position has been dud advice for high-quality companies. Keep asking yourself, “What is the bigger picture?”

People managing funds are investors at heart. They research solid companies in attractive industries that can grow from a long-term perspective. But they inevitably engage in profit-taking and market-timing based on news/rumors, drastically shortening the time horizon. We then become hyper-influenced by analysts’ recommendations and hyper-fixated on valuation metrics. Long-term investing involves holding during downturns, but letting your winners run is equally important.